“Belva Ann Lockwood flatly rejected the gallantry of those who sought to protect women from the more rigorous aspects of life. Denied the right to teach physical education to her female pupils, Lockwood protested until that privilege was granted. Barred later from utilizing a hard-won law degree in many courts, she lobbied for a congressional bill permitting women to argue before the Supreme Court and, on its passage in 1879, became the first woman admitted to practice in that tribunal. In 1884 Lockwood realized that although she could not vote, she could seek public office. By the late summer, before cheering supporters, she became the first woman to formally declare her candidacy for president. In this portrait, Lockwood appears in the robes presented to her in 1908 on receiving an honorary degree from her alma mater, Syracuse University.” -- National Portrait Gallery

The Belva Ann Lockwood papers at Swarthmore have this George V. Buck photo of the portrait autographed by Mrs. Lockwood.

In December of 1911, a meeting of about 40 prominent women was held at Eagle Lodge, the home of Mrs. John A. Logan, to discuss honoring then 84 year-old Mrs. Lockwood with a portrait of herself. (See The Washington Post, To Honor Mrs. Lockwood, Dec 8, 1911.) Another meeting was held at the New Willard Hotel on February 6, 1912 to further the project. Mrs. Nellie Mathes Horne was commissioned to paint a life-sized portrait of Belva Lockwood. (See The Washington Post, Feb. 7, 1912. ) Invitations were sent out. Mrs. Howe arrived in Washington in January of 1913 to finish the portrait and, a month later, it was ceremoniously unveiled at the New Willard on February 10, 1913. At the unveiling Mrs. Lockwood announced her retirement from the practice of law, wishing to devote her time to various other pursuits. (See The Washington Star, Feb. 11, 1913.)

The portrait was first displayed at the Willard but was soon loaned to the National Museum which would become the Smithsonian. It was given to the National Collection of the Fine Arts in 1917 and transferred to the National Portrait Gallery in 1966.

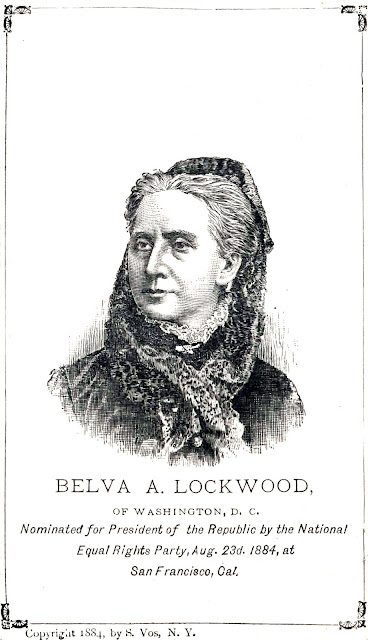

Mrs. Lockwood was the candidate for President of the United States from the National Equal Rights Party in 1884 and 1888; As a woman, Mrs. Lockwood could not vote in 1884 or in 1888 but as she put it, “I cannot vote but I can be voted for.” Here's the announcement of Mrs. Lockwood's candidacy in 1884.

This 1884 Punch cartoon by F. Opper entitled "Now Let the Show Go On!" shows Belva Lockwood as the "Political Columbine" joining Benjamin Butler, as the "Political Clown", representing The Anti-Monopoly Party and the Greenback Party. Democrat Grover Cleveland, not shown, won the election. Belva Lockwood received 4,194 votes.

The 1884 campaign spawned the phenomenon of “Belva Lockwood Parades” in which men would form “Belva Lockwood Clubs” and dress up as women to march down the street in satirical support of Belva Lockwood. This one held in Rahway, New Jersey, was captured by a staff artist at Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper:

Looking back in 1903 Belva described the situation this way in her article in the National Magazine entitled “How I Ran for the Presidency.”

Belva Lockwood's grave can be found, with some difficulty, at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC.

For a more extensive (and contemporary) biography of Belva Lockwood, See: Lockwood, Mrs. Belva Ann, in American Women, by Livermore and Willard, 1897.

Belva A. Lockwood,

of Washington, D.C.

Nominated for President of the Republic by the National

Equal Rights Party, Aug. 23d. 1884 at

San Francisco Cal.

The 1884 campaign spawned the phenomenon of “Belva Lockwood Parades” in which men would form “Belva Lockwood Clubs” and dress up as women to march down the street in satirical support of Belva Lockwood. This one held in Rahway, New Jersey, was captured by a staff artist at Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper:

New Jersey.— The Humors of the Political Campaign—

Parade of the Belva Lockwood Club of the City of Rahway.

“A lively and amusing feature of the campaign was the Mother Hubbard Clubs, composed mostly of young men dressed in women's clothes, who made speeches and sang songs, always representing the candidate, and which the newspapers published as an actual verity. The most noted of these was the club at Rahway, New Jersey, which was pictured at large in Frank Leslie's, the Broom Brigade of New York City, illustrated in the World, and the Mother Hubbard Club at Terra Haute, Indiana, which actually did some creditable work.”

This rebus-ribbon was part of her 1888 run for the presidency.

“At age fifteen, Belva Lockwood taught in a rural one-room school near Niagara Falls, New York. After realizing that male teachers were earning twice as much as she was for doing the same job, she spoke out in public against gender discrimination. Teaching ultimately helped Lockwood understand how to appeal to different groups of voters. When she ran for president a second time, in 1888, she had satin ribbons with a rebus puzzle made for her campaign. The ribbon phonetically pictures the name Belva Lockwood with images of a bell, the letter ‘v,’ a lock, and a log of wood, thereby assisting illiterate voters.

A tireless worker, Lockwood testified in Congress, helping to achieve the 1872 equal pay bill for government employees. Her efforts also led to legislation enabling married women in the District of Columbia to retain their property rights and the passage of a bill to empower widows to claim full guardianship of their children.” - SAAM

The 1888 campaign brought forth a song entitled “Belva, Dear” by M. H. Rosenfeld published in the New York Morning Journal. The songs begins:

We'll not vote for Ben nor Grove,

Belva, dear; Belva, dear;

For our choice is you and “Love.”

Belva, dear; Belva, dear;

Ben is Benjamin Harrison and Grove is Grover Cleveland. “Love” is Alfred H. Love who was at first nominated as vice-presidential candidate to run with Belva Lockwood. Love turned down the nomination and Charles Stuart Weld took his place. Benjamin Harrison won and Belva Lockwood did not get a significant number of votes, prompting this short poem in the Indianapolis Journal in November 1888.

Their Efforts Were in Vain

While waiting men the count did watchWith mingled hopes and fears,Inspired by the party interest,Where were the Belva-dears?Returns were read for Harrison'Mid wild, excited cheers;The Clevelandites, too, had their share—What of the Belva-dears?What mattered if they met and spoke,Disdaining husbands' sneers?Their ballots showed not in the count,These Lockwood Belva-dears.

In her time, Belva Lockwood was known for the tricycle she rode around Washington. Jill Norgren includes this 1882 Washington Post image of Belva on her tricycle in her 1999 article in the Journal of Supreme Court History, Before It Was Merely Difficult: Belva Lockwood’s Life in Law and Politics.

"Belva Lockwood was known in Washington as a successful women attorney. She adopted the tricycle as an efficient means of getting around the capital. An 1882 Washington Post column mused; 'In sunshine or in storm may her familiar form be seen flying up the Avenue on her three-footed nag, her cargo a bag of briefs for the D.C. Superior Court or a batch of original invalids for the Pension Office.'" -- Jill Norgren, 2007

See Familiar Characters, in the Washington Post, March 5, 1882, Page 2. Two days later a poem appeared in The Post addressed to the artist Sid Nealy and signed “B. A. Lockwood” in an article entitled Belva Mounts Her Pegasus.

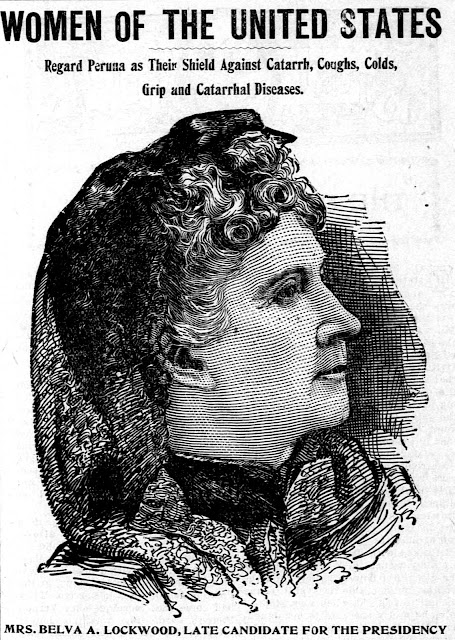

This photo of Belva Lockwood has had many uses, including advertising...

This Peruna ad featured a testimonial by Mrs. Lockwood.

Another ad for Peruna called her “The best known woman in America.” And an ad for Fairy Soap called her “The most prominent woman lawyer in the world.”

When Mrs. Lockwood died on May 19, 1917, this photo accompanied her obituary in The Evening Star.

Belva Lockwood's grave can be found, with some difficulty, at the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, DC.

Belva Ann Lockwood

Born Oct. 24, 1830

Died May 19, 1917

For a more extensive (and contemporary) biography of Belva Lockwood, See: Lockwood, Mrs. Belva Ann, in American Women, by Livermore and Willard, 1897.

No comments:

Post a Comment